Implementing narrowing

This post is on implementing the type-narrowing feature from TypeScript into my own type-checker ezno.

What is type narrowing?

TypeScript is an extension to JavaScript. In JavaScript every value has a type.

console.log(typeof 4) // number

console.log(typeof "hiya") // string

console.log(typeof false) // boolean

console.log(typeof { a: 2 }) // object

console.log(typeof (() => 3)) // function

console.log(typeof 4) // number

console.log(typeof "hiya") // string

console.log(typeof false) // boolean

console.log(typeof { a: 2 }) // object

console.log(typeof (() => 3)) // function

We can reason about values and variables before run-time using type checkers and types annotations.

print_type(2) // 2

function func(param: string) {

print_type(param) // string

}

print_type(2) // 2

function func(param: string) {

print_type(param) // string

}

There are many places where types annotations can exist. These annotations can inform the checker about the shapes of the values a reference can have so that the checker program can report errors and more ahead of time.

There are other ways types are realised within the checker aside from annotations. One of them is the information present in the assumption of a condition holding in a branching structure.

Here we see that because of the condition param === "hi", we can narrow in on the type string to knowing that value of param in the branch is a constant string "hi".

function func(param: string) {

if (param === "hi") {

print_type(param) // "hi"

}

}

function func(param: string) {

if (param === "hi") {

print_type(param) // "hi"

}

}

Why type narrowing?

This functionality enables a few things

1. We can branch on the tags of sum types

type Kinds =

| { tag: "person", name: string, age: number }

| { tag: "vehicle", horsepower: number }

function print_kind(item: Kinds) {

if (item.tag === "vehicle") {

print_type(item.horsepower)

}

}

type Kinds =

| { tag: "person", name: string, age: number }

| { tag: "vehicle", horsepower: number }

function print_kind(item: Kinds) {

if (item.tag === "vehicle") {

print_type(item.horsepower)

}

}

2. We can filter out null values through early returns

function print(item: MyObject | null) {

if (item !== null) {

return

}

console.log(item.name)

}

function print(item: MyObject | null) {

if (item !== null) {

return

}

console.log(item.name)

}

and through short-circuiting operators

typeof x === "string" && x.contains("blue")

typeof x === "string" && x.contains("blue")

3. We can detect exact values (here through a free-variable)

let x: string = "";

function print() {

if (x === "hello") {

// ...

// Warning here!

if (x === "hello") {

}

}

}

let x: string = "";

function print() {

if (x === "hello") {

// ...

// Warning here!

if (x === "hello") {

}

}

}

4. Checking data exterior to the program

const item = await fetch("./my_api.json");

if (typeof item.property === "string") {

console.log(item.property);

}

const item = await fetch("./my_api.json");

if (typeof item.property === "string") {

console.log(item.property);

}

Effectively it enables

- Using properties of data of varying structure

- Using properties of data of unknown types

- Catching truthy values

The idea behind narrowing is to pick a new type (that is a subset of the current type) based on properties enforced by the condition.

We can do that given we have in the context

- Some unknown type: parameter or from some external source.

- A conditional expression

Information on types

Now we know what narrowing is and why it exists as a feature, we can see how we may go about implementing it.

Ezno is not a rewrite or port of the TypeScript Compiler (TSC), so this implemention was built on my own intuition and may be completely different to how it is built in TSC. We can see thought that it matches much of the same functionality of TSC.

The first thing to know is how Ezno represents types. Here parameter types and external types are wrapped in special types similar to generics. These wrapper types therefore have a flag and as they are new types, a unique TypeId.

#5: string

...

#1232: Parameter { name: "param", backing: #5 }

#5: string

...

#1232: Parameter { name: "param", backing: #5 }

When we use a parameter type we add more information onto it. These information is achieved under Constructor. So param === "hi" and param.length become Constructor::Operation { operation: StrictEqual, lhs: #1232, rhs: *"hi"* } and Constructor::Property { lhs: #1232, rhs: *"length"* } respectively. We can reduce these constructors to their base types of boolean and number when using them but storing them, we hold onto these richer properties.

Narrowing: the implementation

The main narrow function takes the type of the expression and returns a list of new constraints for various values.

For example given our above example, we have something like these (described in TypeScript rather than Rust).

function narrow(expression: Parameter | Constructor) -> Map<Id, Type>;

narrow(*c == 3*) -> [[*c*, Constant(3)]]

function narrow(expression: Parameter | Constructor) -> Map<Id, Type>;

narrow(*c == 3*) -> [[*c*, Constant(3)]]

Producing a narrowed map is implemented in the single file

checker/src/features/narrowing.rs.

The narrow implementation is quite simple: we take our Parameter and Constructor objects and figure out narrowed type-to-type key-value entries in our returned map.

Operator Constructors

There are many kinds of expressions that give more information about values

a // a is truthy

a === ? // a now has the type of the RHS

typeof a == ? // a now has a type defined by

a[prop] == ? // a has prop of type

prop in a // a has a prop

a instanceof ? // a is an object with prototype

a // a is truthy

a === ? // a now has the type of the RHS

typeof a == ? // a now has a type defined by

a[prop] == ? // a has prop of type

prop in a // a has a prop

a instanceof ? // a is an object with prototype

Here each has types that are structured as

*parameter*Constructor::Equal { lhs: *parameter*, rhs: ? }Constructor::Equal { lhs: Constructor::TypeOf { operand: *parameter* }, rhs: ? }Constructor::Equal { lhs: Constructor::Propery { operand: *parameter*, property: *prop* }, rhs: ? }Constructor::HasProperty { lhs: *parameter*, rhs: *prop* }Constructor::InstanceOf { lhs: *parameter*, rhs: ? }

When we are passed one of these constructors we can return a key value pair. There is more going on but it is almost as simple as the following

fn narrow(ty: TypeId) -> HashMap<TypeId, TypeId> {

// ...

if let Constructor::InstanceOf { lhs, rhs } = ty_object {

return HashMap::from_iter([(lhs, rhs)]);

}

// ...

}

fn narrow(ty: TypeId) -> HashMap<TypeId, TypeId> {

// ...

if let Constructor::InstanceOf { lhs, rhs } = ty_object {

return HashMap::from_iter([(lhs, rhs)]);

}

// ...

}

While roots are relatively simple, we have to do a bit more when the lhs is a union type.

Union filtering

If we have x: string | number (a union type) and a check of typeof x === "string", we want to find types from the [string, number] vector that pass the check (in this case string).

Union types are represented as trees, so we do a recursive walk yielding types that pass the filter to a found array.

There are (currently) six kinds of filter

HasPropertyHasPrototypeIsTypenull | undefinedFalsyNot<Filter>

These each yield true or false for each type passed by the filter. If true we add that field to vector to build the new, filtered union type.

Logical operations: appending ands

Conditions can be combined. One of those is the logical and &&, which can requires the two operands to hold.

To narrow these we collect each side and concatenate the left cases with the right cases. Here isNumber(a) -> a is number and isString(b) -> b is string get combined to yield a narrowed result of isNumber(a) && isString(b) -> [a is number, b is string]

if (isNumber(a) && isString(b)) {

a // is number

b // is string

}

if (isNumber(a) && isString(b)) {

a // is number

b // is string

}

Logical operations: or

The other logical operator is the inclusive or: ||. This requires a bit more handling. The following if body can run with a is boolean and b is string therefore we can make no conclusions about a (and vice versa).

if (isNumber(a) || isString(b)) {

a // is ?

b // is ?

}

if (isNumber(a) || isString(b)) {

a // is ?

b // is ?

}

Here we find the keys of the narrowed maps to be disjoint and so produce an empty narrowed map

However, if both operands of the logical operator yield a key-value pair for the same LHS parameter type we can union the results.

if (isNumber(x) || isString(x)) {

x // is number or x is string

}

if (isNumber(x) || isString(x)) {

x // is number or x is string

}

x is number --\

|---> x is number | string

x is string --/

x is number --\

|---> x is number | string

x is string --/

You can see this merging here

Logical operators: negation operators

The final logical operation is negation. We control this through an additional parameter in our narrow function. When the negate parameter is true it mostly disables narrowing, but as we will see later we it can be useful with additional intrinsic types.

function func(x: number) {

if (x !== 3) {

x // is not 3?

}

}

function func(x: number) {

if (x !== 3) {

x // is not 3?

}

}

Negation is not always through the bash (!) operator. We sometimes see it crop up implicitly through else branches.

if (isNumber(x)) {

// ...

} else {

x // is not number

}

// as this is equivalent to

if (isNumber(x)) {

// ...

}

if (!isNumber(x)) {

x // is not number

}

if (isNumber(x)) {

// ...

} else {

x // is not number

}

// as this is equivalent to

if (isNumber(x)) {

// ...

}

if (!isNumber(x)) {

x // is not number

}

Logical operators: De Morgan's laws

We can combine negation with the && and || operators. Those familiar with De Morgan's laws may know what we can do here.

If we have a !(a || b), we can treat it as !a && !b. So for the following we find the following value for x in the else branch

if (x === 2 || x === 10) {

} else {

x // is not 2 and not 10

}

if (x === 2 || x === 10) {

} else {

x // is not 2 and not 10

}

This can be seen here

We have the same logic for treating

!(a && b)as!a && !b

Aside: logical operation representation

For those who may be digging through the code wondering where Constructor::LogicalOr or Constructor::LogicalNegation is. There is a interesting short-cut taken by the compiler in representing these types.

We do this by realising the following.

!b ≡ b ? false : true;

x || y ≡ x ? x : y;

x && y ≡ x ? y : x;

!b ≡ b ? false : true;

x || y ≡ x ? x : y;

x && y ≡ x ? y : x;

So the actual represention of these types is Constructor::ConditionalResult.

Sometimes we want this lifted form, so there are helper methods for finding these.

Control flow

As mentioned above, when checking the else branch, we take the condition in the truthy and run narrowing again with negate = true this time.

// ↓ ↓ ↓

let negate = true;

// ↑ ↑ ↑

let values = super::narrowing::narrow_based_on_expression_into_vec(

condition,

// passed here

negate,

environment,

&mut checking_data.types,

&options,

);

// ↓ ↓ ↓

let negate = true;

// ↑ ↑ ↑

let values = super::narrowing::narrow_based_on_expression_into_vec(

condition,

// passed here

negate,

environment,

&mut checking_data.types,

&options,

);

This may be duplicate type scanning and maybe could be made faster in the future

Building new objects

For the following

function func(obj: any) {

if (typeof obj.property === "number") {

// ...

}

}

function func(obj: any) {

if (typeof obj.property === "number") {

// ...

}

}

We build up a new object { property: number } for obj.

What to do with the narrowed values?

Now we have a map of narrowed values, we then store these on the context local to the branch body.

At several stages, when using the reference, we swap out the backing type with a narrowed value from the context.

pub(crate) fn get_value_of_variable(...) {

/// ...

let current_value = current_value.or_else(|| fact.variable_current_value.get(&on).copied());

if let Some(current_value) = current_value {

// info = property on context

let narrowed = info.get_narrowed_or_object(current_value, types);

if let Some(narrowed) = narrowed {

return Some(narrowed);

} else {

return Some(current_value);

}

}

/// ...

}

pub(crate) fn get_value_of_variable(...) {

/// ...

let current_value = current_value.or_else(|| fact.variable_current_value.get(&on).copied());

if let Some(current_value) = current_value {

// info = property on context

let narrowed = info.get_narrowed_or_object(current_value, types);

if let Some(narrowed) = narrowed {

return Some(narrowed);

} else {

return Some(current_value);

}

}

/// ...

}

Thus concluding how narrowing is implemented:

- Have types that store information about operators etc

- Visit the condition type, producing a map of narrowed constraints. Apply logical operator rules and run filters

- Store that information in the branch context

- When looking up a type of variable etc, look for a narrowed type

More narrowing

We have covered that basics of narrowing. Here are some other interesting things I also implemented.

Explicit type annotation type guards

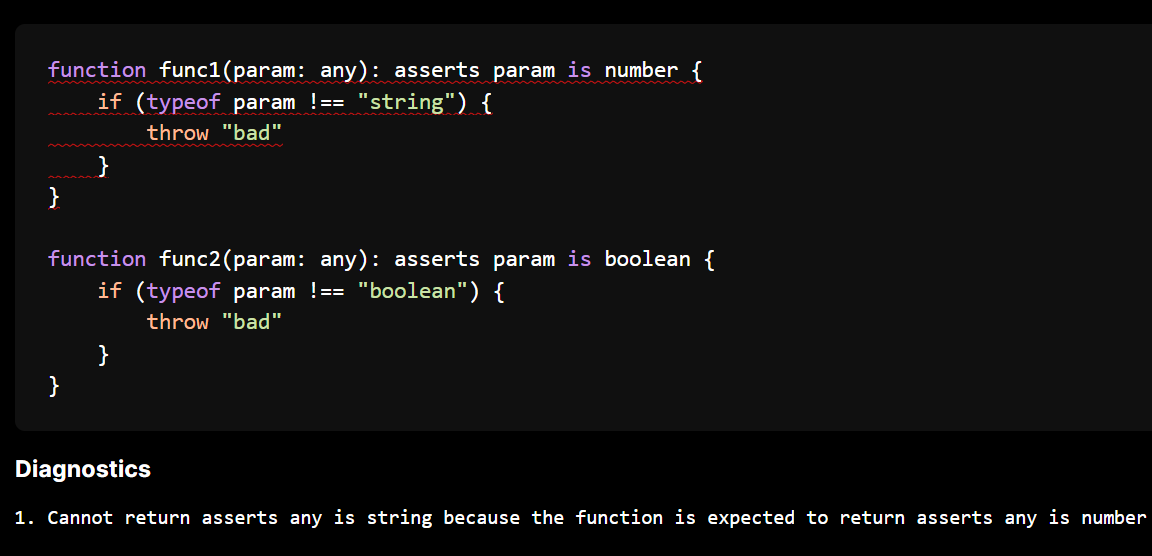

While we can write expression type guards, sometimes this functionality is hidden behind functions. To do this we have return type guards.

function isNumber(x: any): x is number {

return typeof x === "number";

}

function isNumber(x: any): x is number {

return typeof x === "number";

}

This works simply again with x being an implict generic. For x is y type annotations, we look up the parameter type of x and use that type. At usage, this is done by specialisation like other generics.

The checker has not be tested on schema libraries like arktype or zod which use return type guards. Other features of the type system are missing to support this

These type guards are synthesised as annotations into a constructor not producible from JavaScript expressions (at the moment 👀). However, because of the Constructor type, we get inferred type guards for free.

We also can check them (a feature TypeScript does not currently have).

This is implemented in type subtyping

Inference of Not intrinsic

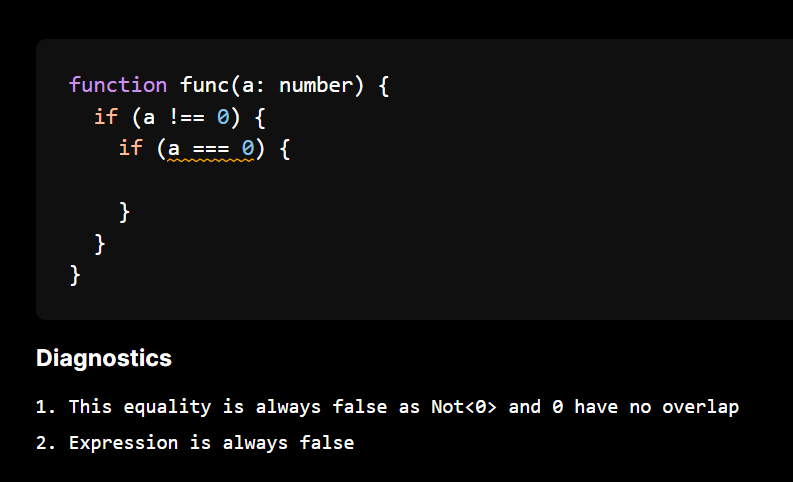

Ezno has additional types that can represent things not possible in TypeScript. One of those is the Not<Type>. You can read more about these additional types in a previous post.

With the Not intrinsic generated by narrowing we can find invariants in the program.

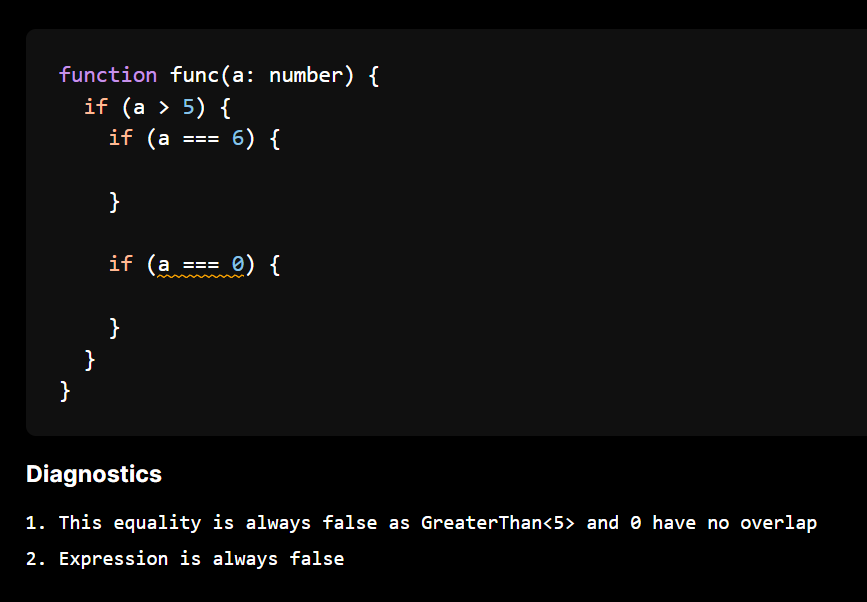

Inference of other number intrinsics

We can also do this for numbers.

Again find out more about these additional types in the previous 'experimental types' post.

Performance and type overhead concerns

Current benchmarking shows roughly 1% of checking time is on building the narrowing map.

Diagnostics: 4320

Types: 48667

Lines: 21990

Cache read: 231.702µs

FS read: 1.620879ms

Parsed in: 28.493175ms

Checked in: 43.683541ms

Narrowing: 400.151µs

Reporting: 903.007µs

Diagnostics: 4320

Types: 48667

Lines: 21990

Cache read: 231.702µs

FS read: 1.620879ms

Parsed in: 28.493175ms

Checked in: 43.683541ms

Narrowing: 400.151µs

Reporting: 903.007µs

The extra intermediate types with deep properties may be a general concern though for performance.

Wrapping up

Hopefully this was interesting short explanation on how I implemented type narrowing. More posts coming soon!